The Clod and the Pebble

I am a clod. And not in the endearing way: lithe, clumsy women stumble into the DJ in their black platforms breaking the beat and causing everyone to turn and look and smile because she covers her mouth with a beautiful innocence. I’m not the kind of girl that can fake innocence. I come from a background of pragmatic experience; my body moves in lumpen unexpectedness. I am the sort of girl that trips over an imaginary crack in the sidewalk and lands with a flump on heavy breasts, hands spread out in front of me like a bear rug. Yes, that’s me: lumps or nothing at all: sprawled out. And then, sometimes you’ll find me standing in busy crowds, terrified to move with my eyes darting back and forth in their saggy sockets. I’m not comfortable in all that bustling and bumping, jagged knees and elbows and chins. Sometimes people interpret this as eccentricity or mystery. Neither, hardly. I’m just a clod in the good old-fashioned sense of “yoick, yoick,” stew and dumplings, and inappropriately blowing spit bubbles out of the corners of my mouth at departmental cocktail parties.

I’m in the Department you see—a kind of low-level professor type in an arcane field populated by the old and the young in an uneasy atmosphere of tender disgust. The cocktail parties make everyone nervous, I guess. They remind one too much of the funeral receptions that had served as job interviews. Forced to compete with one another in the widow’s parlour, blithely spouting platitudes about a man whose heroism was defined by his ability to hold his tenure all the way up to the lip of the grave. Ironically, my interests are so particular that there was little competition for the tiny mid-hall office. It seemed to please them most of all that I was a clod; it put them at ease.

But don’t feel sorry for me. Long ago I became comfortable with my cloddish self. When, at thirteen, I sprouted up and out and began to hunch over in foolish disguise, my father, who had previously thought me only a clumsy child—endearing, yes I was endearing when I was clumsy and rose-faced—he was aghast at my permanent condition. “You’re a clod,” (pronouncing it “load” as if adding weight to that already overburdened short and heavy word). He would say it in disbelief that his own rough handsomeness (he had been a wrestling champion in Russia) had produced this bumpy girl. Later, he seemed resigned to the fact and so I accepted it as well. I like to think he came to, well, almost appreciate it. He would blurt out the observation with a sharp startled newness but he said it as he might say “You’re a woman” or “You’re a communist”: fact, accusation, acceptance, excuse all rolled into one.

But all this is really just a prelude to my confession that I had fallen in love. With the exception of a few predictable gropings in my teenage years I had little experience with the experience of love. There was some slight sensation—a kind of tingling on the back on my tongue—when a pubescent suitor lunged across the park bench and sunk five clawed fingers up to the knuckle into my blouse. But that was hardly love. As I found out later it was hardly lust but a kind of sexual absurdity—a hand slapping buttocks, reaching for the bosom—that middle-aged men and young boys find hilarious and horrendous by turns.

But Matt changed that. He explained things in a nosey twang, breathing across the space of his desk. I don’t remember how it started. I hardly think I did anything to induce his lust except to be expectant and receptive. He must have said a word across his thin lips, or made a gesture with his thin, white-nailed fingers or, perhaps, he simply paused a little too long forcing my eyes upon his gaunt cheeks, his pale complexion and his bespecked, intelligent eyes. Oh yes, I remember my meeting with him. He was sitting behind his neat oak desk, the fourth floor window overlooking a courtyard of hundreds of other windows. We were placed on the same committee; he was the elder colleague.

“Call me Matt,” he said. I did and that strange tingle on the back of my tongue caused me to shake my head like a dog eating peanut butter and he said, “You have lovely chestnut hair. Are the curls natural then?” It seemed a rather personal question under the circumstances (it later occurred to me that this was the way these things were done) but I said yes and before I knew it (really, it’s all such a blur now) we were lovers in all the right ways. We had no attachments, no kids, no pets and no allergies. We worked in close proximity but not in the same building. Neither of us really understood the other’s research so there was always something of a mystery about us. We could never descend into banal conversations about work. Not that we talked much; it was really a sexual affair and I say that with some pride. I would offer up my farm-girl frame: the excessive curving, the fluid flopping as I rolled about for his inspection. He would take off his wire-framed glasses and peruse the depth of my collar bone or sometimes he would simply move over me kneading and squishing as he saw fit, working his weight upon me until I felt thoroughly trodden and wonderfully calm. Yes, this is love, I thought, though we never discussed it. This is a love that builds itself.

But no.

Even my pragmatic Russian parents didn’t prepare me for the sudden crash. In a department where only death and not despair moves people along, in such a department inter-office affairs are a poor choice of recreation. He confessed his infidelity (a student!) and still I clung to him, but he wanted to be clean of me, of us. What could I say? We were colleagues, after all. Regardless of how I acted, whether I attempted suicide or slashed his tires or wrote incriminating memos with stick figure illustrations, we were stuck with one another. Till death do us part, I suppose. I would continue to blow spit bubbles out the side of my mouth and he would continue to pull off his glasses in a grand gesture when he thought he was being particularly clever.

And so we became good friends and over the next couple of years I discovered that our love had been just another affair to him, pleasing and forgotten along the way. His infidelity, however, was unique to me, to us. This we shared. The one bad incident when he frolicked on my overgrown mossy banks as he dipped his toes into the trickling cleanness of a vapid undergraduate. There was only this one messy memory; a moment of confusion on both our parts. Mine was to love a man for what he could not sustain and his was to love completely but so briefly and without memory, without discernment.

I managed to suffer without any large movements and although my reputation as a quiet eccentric grew in the department I was glad to be relieved of the burden of explaining myself. What was there to explain? I carried Matt—such a soft spark of a name, crisp and biblical, an intelligent name in the informal shortening . . . call me Matt he had said—I carried the memory like a sack of potatoes on my back. I refused to carry it on my heart because I was determined to leave that space open for further use, but the back was willing to carry the weight, and, as any labourer knows, it soon felt like a natural part of me.

Matt was an effervescent man, a social personality, professorial in the new school sense. His light brown hair was always cut in a shapely way about his face and he wore stylish clothing in dark blues and light browns. He knew what would compliment his hair, his eyes, the straight lines of his hips. I would watch him move in toward women—truly fascinated by them—and the desire to know them quickly became physical. I noticed how he timed certain touches to the arm or shoulder for the maximum effect. He complimented hair and eye colour. It became clear to me how much he enjoyed the game and, truly, with the weight on my back barely noticed by my ever hunched shoulders, I delighted to see him play. A master. For the brief hours or weeks of his infatuation, his romance, he was all giggles and energy: triumphant. When it ended he was neither sad nor happy but preferred company of a neutral kind and we would often go to the movies or walk along the docks smelling the fish guts and the gasoline.

It was the beginning of summer. June, I think. Matt had been on sabbatical in Florida for the term and had only just returned. He had returned with a fiancée and an elegant party was planned at his house. As a member of the department I had received an invitation computer-printed on fluffy, oriental pulp. The night was as clear as tap water; what stars can be seen in the city were squeezing out their nuclear power. I had just arrived and was chatting to the dean and her husband when Matt saw me and took my coat. The room had divided into quartets of couples gripping their whisky, their white wine, and bobbing back and forth like lawn ornaments. I manoeuvred my way to the kitchen and after some digging in the cupboards was able to make myself a Khalua and milk, watching the ice soak into the ruddy brown colour.

I could see Matt and his fiancée through the French doors. The couple was standing alone under the stars on the back porch. He had her hand in his and was whispering in her ear; she shyly reciprocated by dipping her head to one side. I suppose I was unwanted, but I was eager to find out what this woman, this fiancée, contained—more than any of the other pleasant graduate students, visiting lecturers, and administrative personnel that had briefly pleased Matt.What was about her that might be different or better or bigger or just different?

After a brief introduction which revealed nothing except her vocal tones (a slight twang that melded nicely with Matt’s own tenor string) and occupation (ornithologist), I spilled my untested drink. Matt offered to make me another. In the kitchen, he took my arm and said “She’s the one.” That’s too vague, I thought. All the rebuttals came into my head at once: the one to change him? to complete him? to stay with him? the one to love him? the one that he would love? or was she just the one to say yes? or just the one he had bothered to ask? Perhaps he simply meant that he had won. He had conquered. She must have been a particularly difficult case, I thought. As he continued to expose this affair, looking over his shoulder through the French doors where his fiancée stood, her silhouette wobbling a little through the glass, it became clear that she had been an especially difficult case. Each date, he explained, had to be planned and he had to calculate several moves in advance. Coffee led to a movie to a dinner to live music and drinks; everything moved up the ladder from romance to seduction. It must have been a matter of pride to see her grab the ring and slip it on her finger. Of course, he loved her. In the same way he loved the game, he loved her. It fulfilled him on many levels: sexual, social, perhaps even metaphysical. He played the part of lover with just enough dash of pride and foolishness to make it believable. He had won and she by definition had lost. And now each morning he would see himself in the hallway mirror and admire his capacity for happiness.

We returned to his fiancée and we chatted about movies and Florida and the weather. I sipped my drink and watched the ice bob in the dun-coloured liquid. After a while Matt, still smiling and still fondling his fiancée’s hand, still delirious with accomplishment, suggested we return to the party. But I wanted to give the moment some importance; Matt looked so open and contented the way lovers should when all the pieces—us and you and them and me—are scattered about your feet, showing and waiting to be properly, finally fit together. I wanted to show him how happy I was. I felt that Matt might have loved me a little longer if he had known that I had the capacity to be so pleased for him. So I wanted to finish this moment of romance—the stars burning through the fabric of the night!—with a blessing of some kind. I turned to the fiancée (whose name I had temporarily forgotten) and said that Matt was lucky.

This wasn’t right; it lacked true depth. Damn this ironic age we live in, it sits on the tongue like a warted frog full of bully scoffs and teasing mimics, stifling the true impulse. But I tried to push through it and said, “When Matt left me for one of his seventeen-year-old students, I thought he was incapable of true love.” I took a breath and said with a deep inner earnestness that made my lips tremble, “But, you standing here, I guess, argue against that.” I raised my glass up toward the stars spilling a little, but I didn’t care. “May your happiness build ever upward.”

Perhaps the last bit was hyperbolic but it was unlike me and I was pleased. I heard Matt’s voice. It said, “How much have you been drinking?” I heard him laugh in a nervous twitter. When I turned to him his eyes were on his fiancée and I watched as a deep cloud of fear and failure smothered their colour. “Is this true?” she said. He said nothing. Then, he blinked, and I was surprised by the rush of warm affection I had for him at that moment—the end of the engagement as it would turn out. I felt not a tingling but a gurgling of love to see him in such pain. No; it was a sloshing, a splashing, a powerful liquid love that washed over me as I saw his eyes nervous behind the wire frames already unexpectedly glistening in anger and hurt and humiliation. I loved him more in that one moment than I had ever loved anyone or anything before. All the pieces before you, building toward a heaven. A heaven of some sort. A deep pleasure at least.

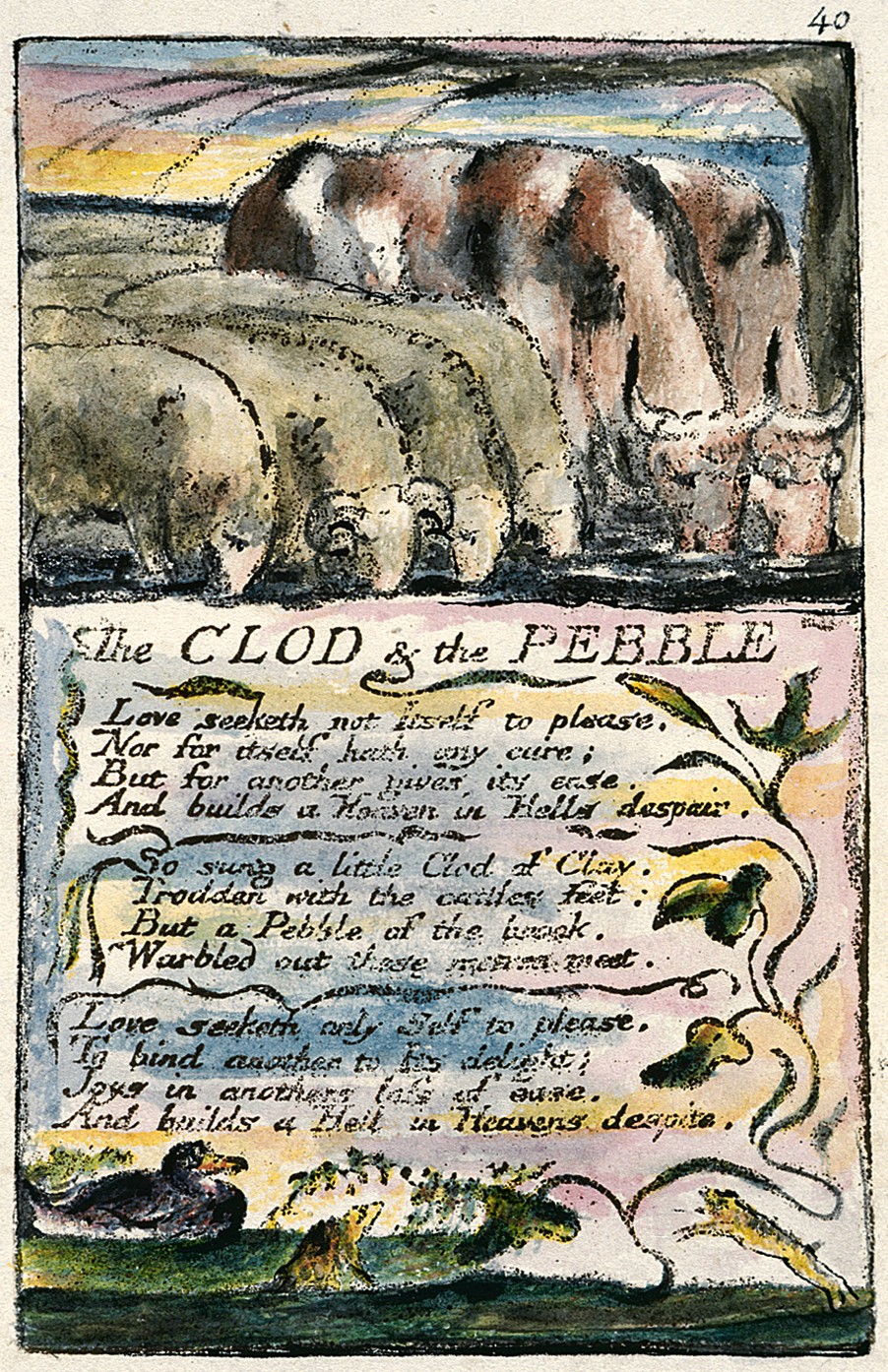

William Blake, “The Clod and the Pebble” (1794)

"Love seeketh not itself to please,

Nor for itself hath any care,

But for another gives its ease,

And builds a Heaven in Hell's despair."

So sung a little Clod of Clay

Trodden with the cattle's feet,

But a Pebble of the brook

Warbled out these metres meet:

"Love seeketh only self to please,

To bind another to its delight,

Joys in another's loss of ease,

And builds a Hell in Heaven's despite."